Just before Christmas 2023, Sinn Féin leader Mary Lou McDonald inadvertently dropped a truth bomb. McDonald suggested in an interview with The Irish Times that she wished to see house prices in Dublin fall to around €300,000 with the goal “to get prices as low as we feasibly can”.

Cue the outrage. Both Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael fiercely reprimanded her comments, demanding to know how Sinn Féin would achieve this policy. Such was the criticism, McDonald was forced to sheepishly backtrack, subsequently clarifying that what she actually meant was the introduction of an affordable housing scheme to sell homes in Dublin for around €300,000.

But what was the problem? Don’t we all want cheaper homes? Haven’t we been told that ‘supply, supply, supply’ is the one true path to affordability? It’s just Economics 101, right? If we relentlessly ramp up supply to outstrip demand, house prices will eventually start to fall back to an equilibrium. It’s just the reassuring dynamics of neoclassical economics at work – like gravity. After all, name me one commodity that doesn’t respond in this way to economics’ iron laws?

Except of course, as the opprobrium directed at McDonald revealed, it’s not. This has never been the intention. House prices simply cannot fall. Why? Well, precisely for the reasons her political detractors retorted. Falling prices would leave tens of thousands of people in negative equity and would collapse the housing market. We have seen that disaster movie before. Indeed, didn’t we spend the past decade and a half since the property crash reinflating prices for precisely this reason?

As housing economist, Cameron Murray, describes in his book, The Great Housing Hijack, there are no examples anywhere in the world where lower property prices have been engineered politically. Price declines only happen as an undesirable side-effect of deteriorating macroeconomic conditions, such as a recession and high unemployment, where there is a significant reduction in the capacity to pay.

This isn’t a particularly radical observation. Intuitively everybody knows it. Approximately two-thirds of Irish households own their own home. With average house prices now topping €430,000, the combined worth of the national housing stock is well over €900 billion. Any politician who proposes to purposely devalue this wealth will simply be ejected, as McDonald likely quickly calculated.

Remarkably, this rather obvious economic conflict is treated as something of a societal omerta. It is rarely openly discussed and, even when it does briefly surface in public debates, it is quickly re-ignored. You would be forgiven for thinking that a majority of the electorate want for nothing more than for developers to flood the market with new housing supply to rapidly deflate property prices. This would be inimical to their own economic interests. Housing is their asset. It’s also frequently their pension.

The inconvenient truth is that if we want to solve the housing affordability crisis, somebody needs to lose economically for somebody else to win. And the losers will certainly not be property owners. Roughly two-thirds of global asset values are invested in property, with residential real estate alone valued at a whopping $287 trillion – almost three times global GDP. By any objective measure, property is by far the most significant store of global wealth.

This situation is particularly acute in Ireland where the state’s response to the collapse of the Celtic Tiger property bubble was to roll out the red carpet to rent-seeking international investor funds to buy up distressed property assets at knockdown prices with the promise of preferential tax subsidies and outsized rack-rent margins. Does anyone seriously believe that these investors want lower prices? More affordable housing equals a very poor investment return.

This is the fundamental contradiction at the heart of the official story of the ‘housing crisis’ and why economics’ sacralised model of supply and demand simply does not apply. Property is both a commodity and an asset. Politicians of course abhor such zero-sum conflicts, especially when property owners are most likely to vote. The political imperative is therefore to ensure property prices remain high while pretending to want precisely the opposite.

Deception

And how is this achieved? The first trick is for the propertied classes to use their prodigious power to present their economic interests as the same as those of society at large, particularly non-property owners. This is mostly accomplished through relentless supply-side propaganda, carefully crafted by minions of well-funded vested intermediaries and ably abetted by a spellbound media – or what Murray calls the ‘Housing Cheer Squad’ – such that everyone is persistently conditioned into believing that only more supply will solve our housing problems.

The apotheosis of this condition is the Irish national obsession with housing targets, where political parties performatively outcompete each other as to who can promise the most on housing delivery. It is something of an enigma to witness a body politic, which relies overwhelmingly on the profit-maximising motives of private speculative investors, setting collective output targets for housing supply. The irony seems to be lost on absolutely everyone.

The reality is of course that developers will supply new housing precisely no faster than what the market can absorb such that prices do not fall. There is simply no way that an industry, increasingly monopolised and financialised by large multinational investment funds and other debt providers, will strive to achieve output targets that devalue their own balance sheets. They are not philanthropists. Their shareholder interests lie in keeping supply scarce.

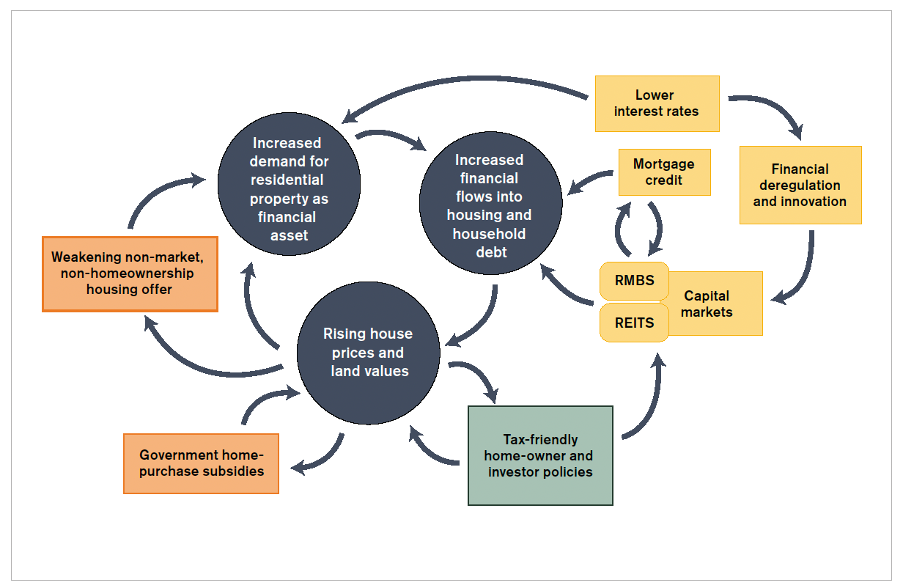

As concluded in the UK’s Letwin Report, the ‘absorption rate’ will always be the primary determinant of new market supply, even when allowing for other constraints. As soon as prices start to fall, supply will be moderated accordingly. And a trigger warning before any ‘Econ 101’ types clutch for their pearls, this is not to say that a surfeit of new supply would not depress prices. It is to explain why that will never happen, at least not voluntarily. The housing-finance feedback cycle ensures that supply is demand.

Source: Josh Ryan-Collins

Upward only property prices are also a precondition for macroeconomic stability. Why else is the government so wedded to the need for demand-side subsidies to keep market prices high? Recently, now-Tánaiste Simon Harris categorically ruled out going into coalition with any party that proposed to abolish these schemes. They know what side their political bread is buttered on. State supports can now reach up to €150,000 per dwelling. If you’ve scrimped and saved to become mortgaged up to the hilt, you’re not going to be best pleased if prices start to tumble. Nobody gets on the mythical ‘property ladder’ to climb down and everybody wants lower house prices, until they own one.

Distraction

Faced with the reality that high housing demand will never be matched with corresponding supply; the Housing Cheer Squad cast around for a villain. And since it cannot be their much-venerated economic theories, it can only be one thing – the government – and more specifically their long favoured bête noire – planning regulation.

Scapegoating the planning system has become a national hobbyhorse, a situation now common to all anglophone countries, with the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council even recently lampooning it as the ‘Planning and Objection System’. The most vocal enthusiasts of this anti-planning agenda are the increasingly influential 'YIMBY' movement; a strange cultural phenomenon imported from Silicon Valley with characteristic evangelism; who insist that if we just sweep away burdensome planning regulations, property owners will magically ‘build baby, build’ and we’ll all live happily ever after.

The intuitive appeal of this simplistic ‘one weird trick’ amongst elite interests is evidenced by the recent establishment of our very own YIMBY think tank, Progress Ireland, the brainchild of fintech billionaires, the Collison brothers. These latest members of the Housing Cheer Squad pass themselves off as just wonky socially concerned liberal progressives with common sense, pro-development and ‘win-win’ technocratic solutions, and the media lap it up. They even co-opt progressive sounding language like ‘affordability’, ‘sustainability’ and ‘liveability’ without of course ever spelling out what they actually mean.

These ideas have received particular purchase on social media amongst disaffected millennials for whom unmet housing demand is a common experience. But you only need to follow the money. Progress Ireland is sponsored by the libertarian-conservative Mercatus Center of the infamous deep-pocketed Koch Industries stable, which the Wall Street Journal once described as "the most important think tank you've never heard of". The real aim, of course, is to ensure public policy incentives are always firmly stacked in favour of the supply-side status quo. In fact, its little more than a facsimile of neoliberal dogma. If it were actually true that relaxing planning regulations lowered prices, the property lobby would long ago have had them cancelled.

Just look at the annual reports of any of our publicly listed major housebuilders. Despite interminable public bluster and poor-mouthing, they do not report to their shareholders that planning regulation is a significant risk to their supply pipelines. Profits are booming. The uplift in land value from receiving planning permission in Ireland can be as high as 20%. This windfall gain transferred to investors from society through the planning system is the underlying incentive to continuously lobby for deregulation. And the prospect of further unearned capital gains is also a powerful incentive to sit tight and speculate, delaying development. This explains the SHD Build-to-Rent mania of the past few years.

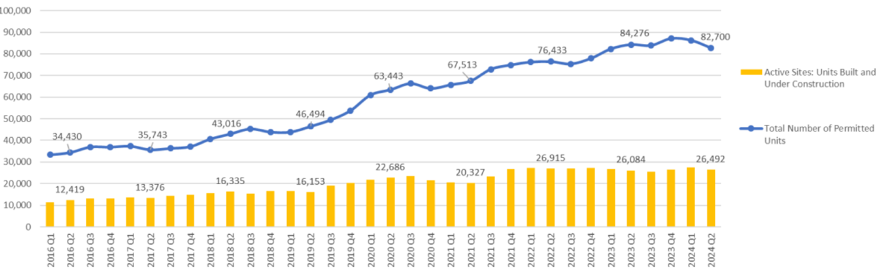

Indeed, a persistent fly in the ointment of the YIMBY panacea is that Ireland does not have a planning permission supply problem. The number of new units being permitted continuously exceeds completions by a very wide margin. But you would never know this. Instead, high-profile media reports of some planning refusal or other are persistently highlighted as further definitive evidence of a ‘broken’ system, ‘blocking’ supply. In Dublin alone, permission is currently in place for a combined total of 82,700 new homes of which 56,208 units have yet to commence. The absorption rate in action.

Source: Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage

Distortion

There is for every complex problem, as H. L. Mencken famously observed, always an answer that is clear, simple and wrong. So, what do we do when we know that market supply can never solve our housing affordability problem? We keep on flogging that dead horse, of course!

With the political-economic imperative to ignore the glaring reality in front of our eyes, academic economics’ departments get busy endlessly producing 'evidence' to distract us from talking about the real sources of housing under-provision. Stung by the rise of ‘supply scepticism’, these simulated studies set out to repeatedly buttress the theory that more supply does indeed reduce prices. Even having the temerity to question the supply doctrine will now have you outed as a ‘supply denier’ engaging in anti-science ‘folk economics’. It's trivially comforting, I’m sure, but it is to answer the wrong question. Its incontrovertible that, all things being equal, new supply reduces prices. That’s the problem.

Even taking these mathemagical studies at face value, they confirm that no plausible rate of supply can significantly reduce housing costs. Estimates vary, but there is a general consensus that a 1% increase in housing stock leads to a theoretical decline in house prices and rents of about 1.5-2%, all things being equal. This means that the government’s much vaunted target of 60,000 new homes per year – even in the vanishingly small likelihood that it can actually ever be met – might, at a push, hypothetically moderate prices by up to 6%. For reference, year-on-year house price growth is currently running at around 10% nationally having increased by over 150% in the past decade with the average house price in Dublin now over €600,000 and rents averaging at €2,500 per month. What was it again that Keynes said about the long run? Oh yeah, we’re all dead.

And we know that in practice all things are certainly not equal in property markets. One study suggests that building 300,000 homes a year in England for twenty years would reduce prices by just 10%. If reducing prices is the goal, new market supply is just about the most ineffective and inefficient way to do it. But, of course, that is not the goal. Other studies counter that this overlooks the price inflation that would have occurred in the absence of new supply. With housing demand projected to significantly increase as a consequence of demographic trends, it is noteworthy that the narrative has now subtly shifted from ‘reducing’ prices to ‘stabilising’ prices. Music to the ears of the Housing Cheer Squad, no doubt.

By some magical serendipity, also fashionable amongst YIMBY-adjacent scholarship and public intellectuals is the disinterring of long debunked ‘filtering theory’. This posits that overall affordability can be achieved indirectly by building high-end, luxury housing – particularly high-density, multi-story towers in high-demand locations – with the housing vacated eventually trickling-down to lower income groups through 'moving chains’. It is difficult to think of an intellectual justification more insidiously legitimating of inequality and obfuscating of the bottom line of the property industry. “Let them eat cake” comes to mind.

By design

Our housing system is not in crisis. It is working precisely as intended, as it has always done. This may be unpalatable to the significant cohort of the population who are the ‘winners’ from the current system but unless we are prepared to be honest about the economic incentives at play, signalling faux concern for the ‘losers’ is little more than lip service. The problem is political, not technical. Ultimately, it’s a class issue. It’s a distribution issue. Of course, this is precisely what the supply mantra seeks to elide. Ironically, to even suggest this, is to be accused of “being ideological”.

In a sense, all of this was learned decades ago with the publication of the 1973 Kenny Report recommendations on the regulation of land prices. There is a reason why it was never implemented. The vast bulk of house price inflation over the intervening years can be attributed to rises in land values which have accrued as unearned capital gains to the propertied classes. If we really want to make housing cheaper, land needs to be treated as the monopoly it is. Pretending that lower prices can somehow be achieved through competitive market forces that simply do not exist only serves to perpetuate the permanent status quo, which I suppose is precisely the point.

Ultimately the reason house prices and rents are so high is indeed about supply – the supply of money. The only way out of our current predicament is to discipline market power and to decelerate the demand for housing as a speculative investment and financial asset through meaningful rent controls, land value taxes, making more efficient use of existing housing stock and the provisioning of a significant bulwark of non-market, decommodified housing options. This is also why that will never happen.

It is also why the Housing Cheer Squad will always fight red in tooth and claw against a constitutional right to housing. Even the recommendations of The Housing Commission, which calls for nothing less than “a radical strategic reset of housing policy”, merely continues the endless merry-go-round of placebo reforms and marginal, half measures. When prominent developers are calling for the full implementation of its recommendations, you can be damn sure that it represents no threat to industry profits. One must only look at its terms of reference to understand why. It was all about supply.

An even more worrying aspect of situating the public debate on housing policy exclusively in the terrain of supply and demand, is that it allows xenophobic reactionaries a political opportunity to whip up anti-migrant, nativist public sentiments to correct supply-demand imbalances. We have seen all too well how acute housing distress has been weaponised to this end. At the same time, nobody has been able to convincingly explain how we achieve housing supply targets while remaining within legally binding carbon budgets. Spoiler alert – we can’t.

Like snake oil, the supply doctrine can never address our housing problems. It never has. Unfortunately, such is its iron grip on public discourse there is little cause for optimism other than to wait for the next inevitable property crash and hope that, unlike the last time, a more enlightened pro-social political zeitgeist emerges from the ruins. Only in a crisis…

“So long as all the increased wealth which modern progress brings goes but to build up great fortunes, to increase luxury and make sharper the contrast between the House of Have and the House of Want, progress is not real and cannot be permanent. The reaction must come. The tower leans from its foundations, and every new story but hastens the final catastrophe”.

Henry George, Progress and Poverty, 1879

Thanks to @DrCameronMurray @jryancollins @pmcondon2 @ricardotranjan for the insights used in this blog.

Brilliant article that applies equally here in Australia. Thank you for such a passionate and intelligent debunking of the supply crap. I think there is a parallel with renewable energy, as shown so well by Brett Christophers in The Price is Wrong, and I try to make the point in one of my Substack posts. The zero marginal cost issue for renewable energy - renewables tend to drive the bid price in market-based electricity systems towards zero - means that we can only get sufficient private investment in renewables with big government subsidies. So why don’t governments build renewables themselves? They should. Just as they should build and own housing.

Brilliant post. Home ownership rate is 65.7%, a good bit below 70% and the EU average.